History Grinds On

The Spokesman-Review, January 6, 1998

More than 800 people lined up for guided tours of the historic flour mill in Oakesdale, Washington, on the 4th of July, as part of MaryJane’s Farm Fair 2009. The mill, owned by the Joseph Barron family for almost a century and now owned by MaryJane Butters, is the only intact flour mill remaining on the Palouse.

“We were overwhelmed with the level of interest in the Old Mill. When our tours began at 10am, there was already a line,” explained MaryJane Butters, organic lifestyle pioneer of MaryJanesFarm of Moscow, Idaho. “We were scheduled to stop at 4pm, but kept the tours going until 7pm because of the demand.”

“The Old Mill needs our help,” she explained. “Due to weather and vandalism, the building requires constant maintenance. Also, we want to open the mill to the public so people can understand and appreciate the history and significance of Palouse agriculture. The Old Mill is a museum celebrating the agrarian lifestyle of this region.”

Flour mills, all similar in size and function to the Old Mill, were built in the 1870 to 1910 period in two dozen Palouse communities, in both Whitman County, Washington, and Latah County, Idaho. Now only the Oakesdale mill remains, the best preserved flour mill in eastern Washington.

Oakesale’s Old Mill was built in 1890, and Joseph Barron, Sr. bought it in 1907. He improved and maintained the intricate machinery, built of hardwood and steel, that cut, ground, separated, and bagged a selection of flours and animal feeds.

In 1909, Joseph Barron, Jr. was born, and at age 18, started working full-time at the mill. He took over the family business in 1955 upon the death of his father. But Barron’s Mill could not compete with the huge centralized flour factories coming onto the scene and closed forever in 1960.

However, Joseph Barron, Jr. could not forget the mill or the milling. He explained that he had “flour in his blood.” He set up a small electric specialty mill in his garage and prepared organic flours and cereals for the new natural foods market. And he refused to demolish the Old Mill or sell the machinery.

Before his death in 2000, Barron found the person to maintain his legacy. He sold both his new electric mill in his garage and the original four-story mill building to MaryJane Butters. She now uses the new mill to grind cereals and flours for sale in her MaryJanesFarm products. And as she promised Joseph Barron, Jr., she is committed to preserving the Old Mill.

The sign at the Oakesdale mill says, “If no one is here, serve yourself.” For decades, customers have. Left their money, took their flour: 100 percent whole wheat with vitamins, minerals and a bit of Joseph Barron’s soul in every bag.

For more than 70 years, the miller of Oakesdale has ground wheat into flour, feeding first the farmers of the Palouse, then their livestock and now, organic diners from Seattle to New York.

Fifty miles south of Spokane, the Old Mill stands along McCoy Creek, where the willows dip and bend. It is four stories tall and 107 years old, full of intricate working milling equipment.

Time has worn down its buhr grindstone, and now, the miller too. Barron got pneumonia last year, bronchitis, emphysema and then heart trouble.

In a new mill across the creek, Barron could mill 500 pounds of flour an hour. But at 88, hefting 50 pound sacks of flour was too much. Maintaining the immense Old Mill, which quit operating 38 years ago, seemed impossible. He considered giving it away to one of the area’s historical societies, but they were too distant or too poor to pay the upkeep. So Barron put both his flour mills up for sale, sifting through the prospective buyers as carefully as he has different kinds of wheat. His only child, Joan Roehl of Kenmore, WA. said dozens of people inquired.

On Dec. 4, the only surviving flour mill of the 19 that once graced Whitman County was sold. Longtime customer Mary Jane Butters and her husband, Nick Ogle, agreed to preserve the Old Mill and to continue milling Joseph Barron’s flour using his new (1960) mill equipment. They kept the name “Barron Flour Mill,” the three-grained hot cereal he invented, even the hand-lettered sign.

To Butters, it’s a perfect extension of her Paradise Farm Organics, Inc. mail-order company in Moscow, Idaho, and her goal of feeding people healthy food.

To Barron, it’s simpler.

“She liked the old stuff and was willing to keep it,” he said.

Barrons have been milling wheat and other grains in Oakesdale since 1907, when Joseph’s father, Joseph Barron Sr., bought the original mill from Harvey Gray for $11,500.

Two years later, Joseph Jr. was born in a living area attached to the mill. There were three blacksmiths, three railroads, a jeweler and a cobbler in Oakesdale then. Young Joseph grew up to the sound of hammers and anvils, of a town building and growing. Then the town got built, farming became more mechanized and the population of 800 slowly slipped to about half.

The Barron’s held on. Joseph had gone to work for his father in the Old Mill straight out of high school in 1927. But the larger mills in Spokane were rapidly taking over. People bought their flour at the supermarket. The gristmills began to die.

The Barrons held on by cleaning seed, storing grain and selling coal. They survived the Great Depression and World War II, when Joseph got a deferment for this work. They survived until 1960, when he closed the mill. Calendars from those years still decorate the office wall inside the mill, above the original company typewriter and safe. Notebooks with farmer’s names scrawled in pencil hang on nails above bins.

“It’s like they just walked away,” Ogle said.

Barron worked for a while for a co-op but shortly returned to his trade, opening the new mill, a modern electric set-up with two mills in a small building behind his house. He began milling and selling organic flour.

“Joseph has adapted over and over again. He survived,” Butters said.

“I was born into it,” he says. “It gets into your blood.”

With a roar like a jet airplane as it starts, Barron’s electric mill uses centrifugal force to explode the wheat berry rather than crushing it. The process helps lengthen the shelf life of the flour, which, according to testers at Washington State University, doesn’t go rancid for two years, a critical element when no preservatives are used.

“It’s the difference between cutting lettuce and tearing it,” Butters said.

What began as a small trade in the 1960s serving hippies and other “health faddists” became a small but steady business. Barron sold rye flour, corn flour, corn meal and cracked wheat. He sold the soft white wheat of the Palouse for pastry flour. But he went to Three Forks, Montana for hard red wheat, which make the best bread.

“It’s a cult flour,” Butters says. “All these women who come to the mill wouldn’t use anything else.”

Joseph’s Flour was not always known by that name. For years, he sold his products under the trade name “Nutri-Grain” until the Kellogg’s Co. bought the name in 1980.

He was selling Joseph’s Flour several years ago when Butters, an organic entrepreneur selling falafel, needed a place to grind her garbanzo beans. Barron agreed to do it. She was immediately enchanted by both his new operation and the old place.

She loved the Old Mill’s woodwork, handrails worn smooth, the knot-free lumber and the function of the mill as the glue that once brought the community together.

“The first time I toured the Old Mill, I was humbled by the grace and grit of their lives.”

He was spending up to $1,000 a year on upkeep of the old place. But it wasn’t until his health started to go that he wanted out.

“I hate to do it. I’ve made many friends and had a lot of good customers who expected good flour.”

Butters says her goal is to continue to let Barron be part of the business. Eventually, they’ll move the mill equipment to her farm, eight miles outside Moscow.

The company offers 10 specialty flours including, kamut®, an heirloom grain that Aztecs grew, millet, spelt, quinoa, brown rice flour and garbanzo bean flour. She also expects to use equipment from both mills to process grains and legumes into organic falafel, tabouli, hummus, pilaf and instant refried beans. Her husband, a third-generation Palouse farmer, has fallen in love with the work.

“It is there in the middle of town reminding people they once were a community, they relied on each other,” Butters said.

Barron’s wife, Ethel, died more than a decade ago and he lives near the two mills with his cat, Blackie. Barron wanders out each morning to the new mill where, as Ogle putters, flour dusts his shoes, his cheek.

“Never lost the place, ” Barron says. “Never lost it.”

Pioneer’s Death Won’t Stop Mill

Joseph Barron Jr.’s last flour mill is on way to Paradise Ridge

Lewiston Morning Tribune, November 18, 2000

By Elaine Williams

The death of a pioneer in the organic food movement on the Palouse has triggered a transition period for the products he created.

Joseph Barron Jr., a flour maker who lived in Oakesdale, Washington, died in Yakima October 27th at the age of 91.

For much of his career, Barron milled wheat grown organically in Montana into such finely ground flour it made baked goods with the light texture of white bread, said Bill London, the editor of the Moscow Food Co-Op newsletter.

Barron’s health had been failing since 1997. He sold the only surviving flour mill of 19 that once operated in Whitman County, and also his 1960s-era mill equipment, in 1998 to longtime customer Mary Jane Butters and her husband, Nick Ogle, of rural Moscow.

“I just like old things,” said Ogle, vice president of Paradise Farm Organics. “It’s recognizing a need to carry on a tradition.”

Joseph Barron’s Flour was sold at places like the Moscow Food Co-op, and in the Oakesdale garage where it was produced.

Just like Barron, Butters and Ogle left the door open and trusted customers to leave payment in a drawer. A price sheet, pencil and paper were left out so patrons could figure what they owed.

Now their three-year lease on the garage is expiring and the property is for sale. Production of the flour will be suspended while the couple moves the mill equipment to their farm on Paradise Ridge near Moscow.

The mill is only about 30 inches in diameter and 3 feet tall, small enough to ride comfortably in the back of a pickup truck.

But parts of the garage that house the mill were constructed around it, and one side will have to be taken out to remove some of the mill hoppers.

Butters and Ogle also have to build a place for the equipment at their farm. “It’s not something you do in a weekend,” Ogle said.

The tradition of flour milled by the Barron family reaches back to 1907, when Joseph’s father, Joseph Barron Sr., bought the original mill from Harvey Gray for $11,500.

The younger Barron began working for his father in 1927. The mill survived the Depression, World War II and competition from larger operations in Spokane until 1960, when the mill closed.

But Barron adjusted to the new conditions by making organic flour for a niche market with a smaller mill set up in the garage, London said.

At the same time, Barron couldn’t bear to dismantle the mill where he started his career, London said.

He put a new roof on it and got it onto the National Register of Historic places in 1980, London said.

The three-story building has hardwood and cast iron equipment. Wooden handles on the machines still gleam from years of being gripped by floury hands, London said.

“It’s a gorgeous thing. It’s a museum of life on the Palouse.”

October 27, 2000

Dear Dad:

I have so many things for which I’m grateful to you and Mom. I know your sacrifices were many in getting me through college. Thank you.

I have cherished memories. Among them are the dancing we shared, beginning with the lessons at Arthur Murray dance studio in Spokane. Our final dance was at Alterra in Yakima six months ago. You looked so handsome in your tuxedo (one of the female residents thought you were a movie star).

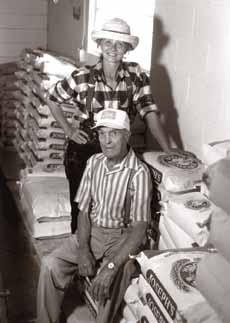

You took such pride in neatness and cleanliness, which was admirable. For example: keeping 25 year old shoes looking new, keeping the “Old Mill” and “Little Mill” in as pristine condition as possible. Your flour sacks were stacked perfectly.

Your August 8th birthday celebrations were so special, with family train rides all over the state. Our final train ride was last month to Mount Hood. One of your great joys was riding in the cab with the engineer. Your knowledge of trains and their routes was phenomenal. I know how much you missed the train whistle going by both sides of the house.

Every Thanksgiving and Christmas your artistic talent would rival the Sunset Magazine’s pictured platter of turkey.

When I smell smoke from the burning of dry leaves, I think of you. What satisfaction you got from tidying up the property.

After Mom passed away, you were at loose ends. We tried to interest you with trips to Hawaii, cruises to Mexico and the Lake Chelan family outing. A note you left behind is priceless. While at Chelan for only two days with you, Sam and I woke up one morning to find a note you had left which said “Like Bob Burns, when that whistle blows, I gotta go”.

Read more about our historic Barron Flour Mill in Wild Bread. Order your copy today →