|

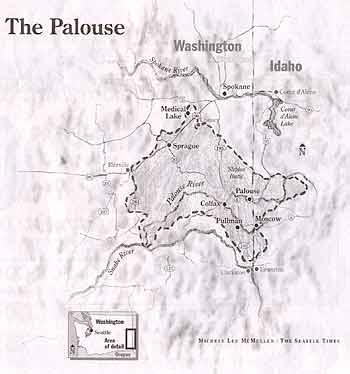

Natural Wonders: Singing the praises of the Palouse PULLMAN, Whitman County - The Palouse, southeast Washington's vast, undulating shag carpet of wheat, is a land of mystery. It is 2 million acres of steep, rolling, nearly treeless terrain, an ocean of crossing currents built of dark soil and flourishing crops.

It is striking to the point of being weird, desolate to the point of loneliness, soft and rounded to the point of being a comfort. It confronts and challenges its denizens, inviting questions: What natural forces did this? Where are the trees? And how on Earth do people live here? Science has teased out the answer to the first question, penning a 2.5-million-year saga of wind and water, and the recurring theme of geology. Why people should live here lurks in the minds of those who sprint across the state for a Washington State University football game or those soldiering here on a fifth-generation family farm. "It has beautiful forms, but it also has loneliness, because there's no people," said Nicole Taflinger, an artist who has painted the Palouse hundreds of times since arriving almost 50 years ago. "It's frightening, this emptiness," Taflinger added. "But at the same time, it's so beautiful and peaceful that I enjoy it a lot. I appreciate it." To live on the Palouse is to take a philosophical position on it. It is a physical and even psychological force to be reckoned with, if only because it is visible from almost any spot between the Snake River and Spokane County, from the Palouse River border of Adams County in the west to Idaho in the east.

Your feeling toward the Palouse landscape is a sort of Rorschach test for how you feel about being here. "I remember vividly driving up the Old Grade and getting to the top," said Tim Steury, referring to the old Spiral Highway from Lewiston, Idaho, up onto the Palouse, where the tawny and arid Snake River breaks give way to folding fields of green, brown or blond, depending on the season. "All I could see was wheat fields. I said, 'This is it?' Now I can't imagine living anyplace else." Twenty-six years later, editing Washington State Magazine and cultivating 75 varieties of cider apples on a small Idaho farm, Steury has come to a new admiration of the landscape. It hits him every time he points his car north out of Moscow, Idaho, and summits Bald Butte. "I feel - I'll try not to be cliché, I'll try not to be maudlin - exhilarated," he said. "It's the most beautiful place in the world. That's my spot, right there. Because there's so much diversity and so much hidden."

A parched yet fertile landIt is improbable enough to have people here. It is even more improbable that these hills should be here to begin with, let alone grow wheat the way they do. The native Palouse Indians, who lent their name to the region and the spotted Appaloosa horse, believed the hills were scooped up by coyote to get the upper hand in a race against turtle. Geologists hold that the hills started in Canada, where repeated glaciers

of the Pleistocene epoch scoured granite and metamorphic rock into millions

of cubic yards of a fine flour. Meltwater washed it away, dumping it into

a massive lake near what is now Missoula, Mont. After the waters came the winds. They blew out of the southwest, carrying huge plumes of dust 40, 50, sometimes more than 100 miles before dropping it in soft piles of loess hundreds of feet thick. To this day, those same winds blow straight out of Wallula Gap and create traffic-stopping dust storms. "We've been calling that the engine of the Palouse," said Alan Busacca, a WSU geologist and soil scientist. "It's the gun barrel pointed right at the Palouse, and it was filled with the same sediments. The winds howling through the Wallula Gap and up over the Horse Heaven Hills have been shedding dust on the Whitman County area for 2½ million years." For those soil particles to travel so far, they must be just the right size to be held up by the wind - - less than 60 microns, or about half the width of a human hair. And once they are on the ground, their size creates a perfect soil pore for holding water. Bigger, sand-sized particles would let water pass right through; smaller particles make clay. The Palouse soil holds water so well that farms can receive as little as a dozen inches of rain a year. Yet it is some of the best dry-land wheat yields in the world. Whitman County has been the top wheat-producing county in the country every year since 1978. Last year, it averaged 78 bushels per acre of winter wheat, the main crop, almost twice the national average of 43.5 bushels per acre.

But what water and wind bring, water and wind take away. Over the millennia, water washed the Palouse's carpet of soil into watersheds carved and sculpted over millions of years into the region's underlying basalt. Snow and freezing and thawing on the lee sides of hills created landslides and left steep, arc-shaped scars that gave the landscape the look of wheat-covered dunes. Farming, by stripping the ground of plants and organic matter, made the region one of the most erosive in the world. In the 1930s and '40s, as much as 100 tons of soil could be washed from an acre in one storm, said Roger Veseth, extension conservation tillage specialist with WSU and the nearby University of Idaho. Nearly half of the region's soil has been lost. Farmers, urged in part by conservation programs tied to federal farm payments, have taken to fighting erosion with different tillage systems, crops and conservation reserves. Many farmers also have planted millions of trees over the years, but newcomers still find the vistas wanting. Outside of the occasional draw and leeward slope, there's not enough rain for trees, even if there is just enough to grow some of the most spectacular wheat crops in the world.

'Makes you want to grow food'A lack of woody greenery can be hard on a newcomer like Darrell Hubbard Jr., a WSU communications and business student from Skyway, who came two years ago without first visiting the campus. "It was a culture shock," he said recently in the school's African American Student Center. "I've been living in Seattle all my life, so I'm used to trees and green. It was just brown. In a way, I'm still getting adjusted." Others find a mix of landscape-fueled inspiration and the economic hardship

of rural life.

"The feeling I got there after a while was the feeling of a cul-de-sac and no opportunity," he said. MaryJane Butters, a Utah native, is at home here, arriving in 1983 to farm and falling in love with a soil that crumbles easily, even after a rain storm, "and you can smell it, and it smells good." The road to her farm descends from Paradise Ridge, just outside Moscow, and takes in a spectacular southwest vista of recently crewcut fields and the tufts of trees popping up from the region's hidden homesteads. She tends 40 acres of organic wheat and most every kind of vegetable, many of which find their way into a line of ready-to-eat dried foods. In the summer, she cooks and sleeps outdoors in a grove of plums and maples. "Landscape has a personality, it has a weight that you feel about

it, and it affects your behavior even," she said, sitting on the

makeshift furniture of her outdoor living room. Eric Sorensen: 206-464-8253 or esorensen@seattletimes.com. |