| |||||||||||||

|

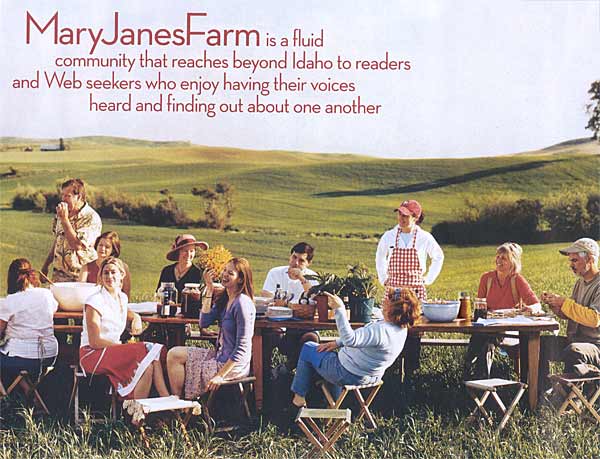

The MaryJane enterprise includes a lively group of friends and workers, overseen by Butters’ husband, Nick Ogle, standing at left, and Butters, seated at right, who keep the farm on course.

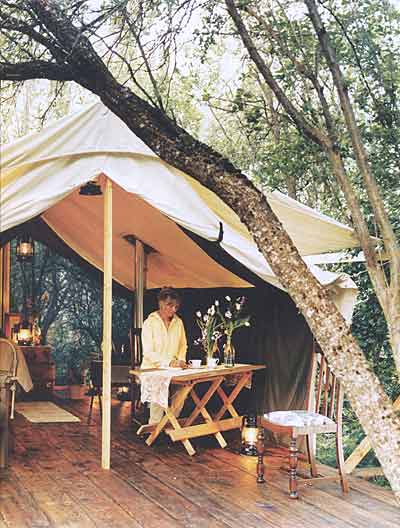

By the time I set off to meet MaryJane Butters this spring, the path to her five-acre farm in Idaho’s Palouse region was becoming a well-traveled road. People who hadn’t made the actual trip were already up on all things MaryJane from her Web site (maryjanesfarm.org), her magazine (MaryJanesFarm), her line of high-quality organic foods, stories about her in national publications, and the publicity surrounding a $1.35 million book deal for MaryJane’s Gathering Place, a forthcoming compendium of the MaryJane approach to life. Welcome to overkill country, I thought, as I drove through the smoothly contoured hills of the Palouse, a landscape whose seductive beauty conceals a monoculture of chemically nurtured wheat. Was I wrong to worry that the MaryJane Butters who poses so fetchingly and so frequently in her magazine with her hand on a plow or her arm cradling a bushel of vegetables might also be way too scenic to be true?

Indeed I was. Instead of being urbanized by what she has learned about marketing, networking, and publicity, Butters has ruralized and personalized everything from the Internet to magazine distribution. Her mission is to make it easy for people — especially rural working-class people — to reconnect with the sources of good food and good life. So why wouldn’t she use every tool available to her? If success means that she has had to brand herself, that’s also okay, because there really is a MaryJane behind the name. She may not always wear the trademark suspenders and the long braid (though she frequently does), and she may no longer answer all her e-mails, phone calls, and letters personally (although someone will), but the farm and the business still operate on an intimate scale. And, she insists, they always will. That and the quality of her products are the real trademark. The personal touch begins at the farm, where she and her husband, Nick Ogle, a soulful native of the land that surrounds Butters’ tiny plot, employ about 14 full-time people, most of whom are local folk fired with optimism about sustainable agriculture. They work on the gardens, the magazine, or the book, or they help package the organic foods. If the whole operation invites comparison with Martha Stewart, the analogy stops where the emphasis on the real, human souls at MJF begins. Butters knows that she has reached her personal tipping point, and she worries a little about the consequences of success. What is likely to protect her from a backlash is the community she has created. As we talk about people like Julie Bell, from South Carolina, who does the food styling and the sewing projects for the magazine, or Carol Hill, from Moscow, Idaho, who designs it, Butters admits that when she stops to consider how much all these people have helped her with her dream she is overcome. “All I can do in return,” she says finally, “is to help them with theirs.”

Dreams are MaryJane Butters’ business, and she has always pursued them without pausing to consult conventional wisdom. In 1993 when she needed money for her business, she figured out how to do her own public stock offering and raised $500,000 from 25 investors. The initial dividends were paid in the form of the farm’s products. To close the circle of business, magazine, and farm, Butters invites her investors to the farm to do a little hoeing and often profiles them in the magazine.

Her approach to journalism is equally inventive. The magazine promotes the MaryJane line of foods and tells readers how to make quick nutritious meals with them. It also draws attention to products made by other rural businesses. There are plenty of reader testimonials, how-to projects, inspirational poems and essays, news bits, and homemaking tips. There are no ads and no subscribers; some features are recycled from issue to issue; “regular” columns may or may not appear; and readers are encouraged to help increase circulation: if they drop an issue off at their local store, they are reimbursed with another issue. It’s the homespun touch again, but it can have large-scale consequences. After her magazine distributor warned her that Wal-Mart wouldn’t be interested in carrying her publication, Butters called around until she got the name of a Wal-Mart executive who would talk to her. She followed up with an issue and a letter, and Wal-Mart was won over. That’s a particularly impressive conquest when you consider that if MaryJane Butters ran the world, rural women would be sewing aprons and cooking fresh vegetable tarts instead of shopping at Wal-Mart for fast foods and ready-made goods. Which is of course why she wanted her magazine in the big store to begin with. “These rural women are the forgotten people,” she says, but she hasn’t forgotten them. She wants to encourage the ones who are already converts to her brand of quick healthy eating and domestic crafts and to convince those who are still microwaving junk and watching TV. She has refused to do a tour when her book is published in the spring of 2005. Instead she hopes to take it into small towns and get together in women’s homes to explain how cooking and eating organically can be done on a tight budget. Don’t tell her that these people won’t read books. She’s certain they’ll read hers. After all, who else has bothered to reach out to them?

Will she go on TV to spread the word? Butters has invited her readers to give their opinions (they’re against it), and says that she may do a few guest appearances and let it go at that. “TV has ruined people’s lives,” she says. “They no longer sew or go for walks. TV has done that.” Although she is no longer a practicing Mormon, Butters has a powerful belief in the self-reliance and community spirit that allowed her working-class Mormon family to survive hard times, and she wants to pass this on. When you think about everything she has accomplished already, you wouldn’t want to bet against her success in transforming the way large numbers of Americans think about how they eat and live. |